Practice Disrupting Theory: Art Rethinking the Subject

by

Valerie A McLean

October 28, 2013

Bracha Ettinger (b. 1948), a painter and practising psychoanalyst, has created a complex body of theory, relating to the mechanisms and development of human subjectivity. As an artist, currently completing a practice-based PhD, I am interested in how Ettinger’s theoretical writings stem not only from her clinical practice but also from her work as a painter. In this paper I give a brief outline of Ettinger’s theoretical articulations: How she, through her working processes, disrupts the main tenets of traditional psychoanalytic thought and imagines a new conceptual framework within which to think about subjectivity and sexual difference. Then, using my own language-based art-work, I explore the ways in which art might provide a space to work at the borders of traditional meaning structures. I examine how practice can circumvent the conventional ideas, and rhetorical limitations, of the subject as embodied in the Lacanian ‘Symbolic’, and patriarchal, spheres of language, culture and the law.

Practice Disrupting Theory: Art Rethinking the Subject

Subjectivity

To be a subject is to be separate, to feel and know oneself apart from others, with a distinct sense of one’s own boundaries. Being separate, by necessity, means that there must be something or someone to be separate from. Psychoanalysis has traditionally posited that the initial separation, which takes place and gives rise to human subjects, is that which we experience from the biological mother at birth. In this instant, we are cut off from our physical connections to another human being and literally, as a result of the birth act, become separate physical entities. However becoming separate is not just about becoming physically separate but also about recognizing ourselves as such. Famously Lacan’s mirror stage outlines the struggle that the developing infant has in perceiving itself as a separate being with a separate body. The apparent unity of the infant’s body in the mirror is at odds, in these early stages of development, with the infant’s rather more chaotic and fragmented inner experience. Subsequently with the acquisition of language a further separation is made away from the preverbal undifferentiated realm of the maternal into a world where the patriarchal ‘laws’ of culture, identity and language hold sway.

For many clinicians and theorists this series of separations is necessary for each individual to successfully take up their place, as civilized speaking beings, in culture and society. It is argued that if such a separation does not take place we are at risk of losing our grip on reality and becoming psychotic. For some feminists this explanation of subjectivity, as arising in large part as a result of our separation from the maternal, has proved to be problematic in its positioning of the feminine. Such an explanation implies that the successful manifestation of the sane subject is arrived at by separation from its feminine m/Other and by implication the male subject embodies, as De Beauvoir states, the ‘universal subject’ which ‘attains substance and meaning only through the exclusion and repression of the feminine’ (De Beauvoir 16).

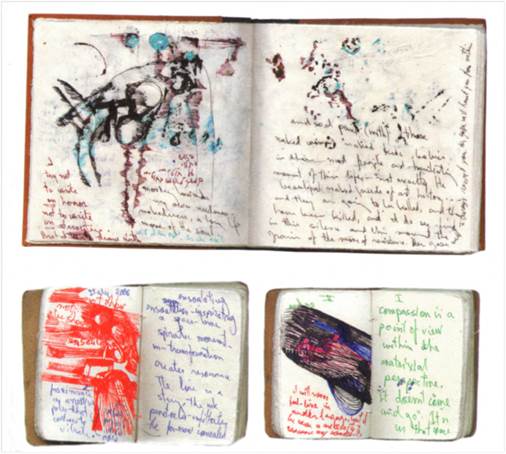

Bracha Ettinger (b. 1948), a painter, practising psychoanalyst and theorist rethinks these assumptions in a way that reclaims the feminine without completely negating the mechanisms of subjectivity as espoused in Freudian and Lacanian thought. Importantly for this discussion her theories have developed as she says from both her clinical and artistic practice and specifically from reflecting on notes and drawings, made in small notebooks, while working in her studio and with her patients, see fig 1. As she made clear, when speaking at the European Graduate School in 2007, it is ‘through looking again and again and reading the notebooks’ that she can ‘elaborate slowly the theoretical’ (Psychoanalysis and Matrixial Borderspace). The evolution of her theories is very much tied up with her practice and, as I hope to show, demonstrates the ways in which practice can literally disrupt theory.

Figure 1: Ettinger, B. Resonance/Overlay/Interweave, The Freud Museum London (2009) – Notebooks. Collection of the artist.

Figure 1: Ettinger, B. Resonance/Overlay/Interweave, The Freud Museum London (2009) – Notebooks. Collection of the artist.

Listen Poetically First……

It is November 2010 and Bracha Ettinger is giving a lecture at the ICI Berlin[1]. Early on in her lecture she asks us to ‘Listen poetically first . . . listen with your musical ears’. In this instant we are immediately made aware that accessibility to her subject matter will require us to step outside of our conventional modes of understanding and interpretation.

Ettinger’s request highlights the necessity to approach her words and theories in a way that is open to the possibility of meanings beyond that conveyed by, and bound to, the framework of conventional language. We sense immediately that her words are attempting to take us somewhere else; somewhere we currently do not have a map for. As Stuart Hall points out the construction of meaning requires two forms of representation the first being a shared conceptual map and the second a shared language (Hall 19). Ettinger‘s endeavor is to map the ‘matrixial’, an originary feminine dimension that has been occluded by the dominance of the phallic. Her difficulty is mapping such a dimension within the confines of the current symbolic structure encompassed as it is in language, culture and the law. This is not an easy task. Susan Stewart, facing a similar problem in her study of nonsense, questions ‘how is it possible for us to talk about something, while at the same time, we are caught up in or implicated in that something?’(vii). There is a need to find other ways to describe, access and experience such dimensions and it is perhaps through mediums such as art and poetry that this can be achieved. As Griselda Pollock points out Julia Kristeva ‘identifies the aesthetic practices of painting, music, dance and poetry – once utilized by institutions such as religion and now secularized – as specialist semiotic agents of transmission between the Symbolic and the presymbolic’ (Ettinger, The Matrixial Borderspace 21).

Ettinger, in her simple request, seems to be inviting us to enter into another psychic space one that can be found in the processes and experiences of poetry, art and psychoanalysis and out-with the confines of conventional language. As Bakhtin points out

The word in language is half someone elses’s […] Language is not a neutral medium that passes freely and easily into the private property of the speaker’s intentions: it is populated – overpopulated – with the intentions of others. Expropriating it, forcing it to submit to one’s own intentions and accents, is a difficult and complex process. (293-4)

So Ettinger asks us to listen poetically as she speaks. In doing so perhaps it becomes possible to circumnavigate the conventional meaning structures of language as espoused by culture and society. In addition Ettinger not only asks that we loosen our grip on such generally accepted meanings but bends and twists the language available to her in ways that infuse it with new meaning. In her writings we are given sign posts to an alternative realm in terms such as ‘matrixial borderspace’, ‘borderlinking’, ‘wit(h)nessing’ and com-passion. As Pollock states ‘Ettinger’s writing is an écriture féminine in Cixous’s sense, even as it elaborates a theoretical intervention. It involves shifts, moves, repetitions, circlings and a poetic language of created terms’ (Studies in the Maternal 13). In Ettinger’s request one senses the struggle to create new sense and form from materials, in this case language, already imbued with layers of culturally assigned meanings. Her process seems to be one of simultaneous deconstruction and reconstruction. In her artwork too Ettinger sees the possibility to create and experience new meanings, knowledge and forms stating that

The painting is a promise to deliver what, up to this specific apparition in this specific painting, was as yet non-knowledge. The matrixial gaze exposes instances of co-birthing and co-fading in which some excess surpassing the artist as subject is suddenly distinguished in the artist’s matrixial borderspace of transsubjective I and non-I. What is captured and given form at the end of this trajectory is that which was waiting for an almost-impossible articulation, in a matrixial time-space of suspension-anticipation. A dynamic indexing a sexual difference in the Real reveals itself the same instant it becomes shareable through the artwork (The Matrixial Borderspace 151).

So it is by means of art works and a poetic interpretation, and use, of language that Ettinger strives to bring her theories into being not only in abstract terms but viscerally through direct experience. In so doing she disrupts and challenges traditional psychoanalytic thought.

Ettinger argues for a twin strand model of subjectivity where an originary feminine dimension, the matrixial, pre and co-exists the unitary phallic. Such a model gives us the possibility of moving away from the limiting binary opposition, and sexual difference, of male and female (self and m/Other). Instead the commonly accepted opposite poles of male and female are placed on the same side of the Matrixial/Male Female pair. As Massumi explains ‘Ettinger carefully emphasizes that this matrixial “femininity” is not the opposite of the phallic masculine. It is more accurate to say that it is the other of the masculine-feminine opposition […] In fact, it is the sexual difference, as against the difference between the sexes’ (Ettinger The Matrixial Borderspace 212)

Ettinger’s theories of the matrixial are based on the fact that for each human subject the earliest, prenatal, stages of development begin in relation to another. The becoming baby and becoming mother co-exist before any separation takes place. There is then for each of us an experience of existing in relation to another before we become separate entities. Ettinger argues that this earliest experience is carried with us, consciously or unconsciously, even after the physical and symbolic separations of birth and language respectively.

While our knowledge and openness to this originary matrixial dimension is largely suppressed after birth Ettinger argues that it does remain accessible especially through encounters with art or in the particular circumstances of psychoanalytic therapy. A term used by Ettinger to describe such an experience is that of ‘subjectivity as encounter’. In order for such an encounter to take place it is necessary for the participants involved to become vulnerable or as she states to fragilise themselves. When she asks us to listen poetically it seems that she is asking us to lower our defenses and become open to the possibility of experiencing subjectivity in this ‘matrixial’ way. Indeed her lecture and installation at the Berlin ICI are part of an on-going series of events which she describes as encounter-eventing.

It is important to note that while comparisons may be drawn between Kristeva’s ‘semiotic chora’ and Ettinger’s ‘Matrixial Borderspace’ there are important fundamental differences. Although both concepts elucidate an originary feminine space Kristeva’s maternal realm is always that which is repressed or foreclosed. For Kristeva as for Lacan it is necessary to completely reject and cut off the maternal and the feminine in order to attain an individual and social identity. This is apparent in her claim that ‘matricide is our vital necessity [….] as speaking beings’ (Kristeva, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia 28). In her writings on abjection Kristeva equates the abject with the maternal body. The subject’s fear of the return of the all encompassing annihilating maternal abject serves to maintain the individual’s separation from it while also producing an almost irresistible fascination with it. ‘But devotees of the abject, she as well as he, do not cease looking, within what flows from the other's "innermost being," for the desirable and terrifying, nourishing and murderous, fascinating and abject inside of the maternal body. For, in the misfire of identification with the mother as well as with the father, how else are they to be maintained in the Other?” The subject is formed out of the necessary traumatic wrenching and separation from the womb at birth. As Kristeva points out ‘the advent of one's own identity demands a law that mutilates’ (Kristeva Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection 54)

Ettinger , however is

categorically opposed to the classical psychoanalytic claim recurrently emphasized by Lacan, Kristeva and others, according to which the womb can appear in culture only as psychosis; that is, that it can only be the signifier for the crazy unthinkable par excellence, and that whatever is thinkable has to pass through the castration mechanism, by which it is separated from its Real-ness, making the womb that which must be rejected as the ultimate abject, and making this abject the necessary condition for the creation of the subject and the psychoanalytic process. (Ettinger Weaving a Woman Artist with-in the Matrixial Encounter-Event 76)

Instead Ettinger argues for an expanded symbolic which encompasses both the

Beyond Utterances

Some of my own voice work also seems to provide a way of exploring the nature of subjectivity[2].

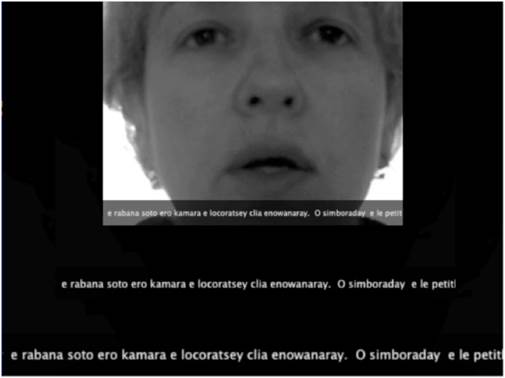

My ‘voice drawings’ while utilising something akin to the structure and sounds of any number of contemporary languages subverts our expectation that it carries culturally recognised linguistic meaning This work involves me speaking ‘fluently’ and calmly in an apparently sensible and, if it could be translated, coherent language. When presented in public either as a video presentation (sometimes accompanied by a transcript of the ‘words’ being spoken, see fig. 2), or by myself in person there is generally an assumption that I am speaking in a ‘genuine’ language albeit foreign to the listener. My own experience of speaking in this way is of producing a non-forced stream of utterances that flow smoothly and require little by way of conscious effort. It feels ‘natural’.

However, despite having the apparent structure and uniformity of a recognizable language, the utterances and sentences I make are, in conventional terms, nonsensical. They have form but no obvious or discernible content. In this respect the work seems to me to straddle the narrow and fragile, culturally determined, threshold between order and chaos, sanity and insanity and sense and nonsense. It seems to teeter at the very edges of these ‘classifications’ and is at any moment capable of sliding into and being swallowed up into an abyss of chaos and madness or, conversely, of coalescing into a coherent stream of meaning. This liminal realm seems, in some ways, to encompass the borderline spaces that many feminists claim women are forced to inhabit as Elaine Showalter states

Women’s social or cultural marginality seems to place them on the borderline of the symbolic order, both the ‘frontier between men and chaos’ and dangerously part of chaos itself, inhabitants of a mysterious and frightening wild zone outside of patriarchal culture (4).

Figure 2: McLean, V. (2010), Still from Degree Show Film, Turama [available at http://www.valmclean.co.uk]

This association of the feminine with the disintegration of sense and order has been a prevailing concern in the work of both feminists and psychoanalysts alike. There are two important issues at stake here. The first is the assumption that anything which lies out-with the accepted symbolic order, or as Griselda Pollock describes it ‘the fortress of the phallic’, is equated with hysteria, madness, psychosis and pathology. The second is the generally accepted idea that this chaotic non-symbolic ‘wild zone’ is directly equated with the feminine. Pollock challenges these assumptions by arguing for the possibility of an ‘expanded Symbolic’ stating

‘Until now feminist thought has banged its head against the walls of phallic logic, without fully realizing that there were walls to this chamber – which is but one, albeit an important one, in the house of a more multiple, expanded Symbolic’ (Ettinger, The Matrixial Borderspace 24).

In Ettinger’s artwork and ‘poetic’ writings we are given in the ‘matrixial’ a sense of, and more importantly the possiblity for, the experience of such an expanded Symbolic realm. As she states ‘we can advance in this way of thinking only if we free ourselves from the compulsion not only to disqualify as mystical or psychotic whatever lies beyond the phallic border’ (Ettinger Weaving a Woman Artist 73).

Likewise I see in my own ‘language’ work the opportunity to experience and embrace a wider field of meaning. For me the experience of speaking in this way is hugely liberating. I am expressing myself in a manner that circumvents the limitations of language. As a result I am much more aware that my voice and vocalizations are rooted in the physical mechanisms of my body. The tyranny of making sense ironically gives way to an experience of a greater feeling of coherence and unity between my mind and body. In many ways I see it as pushing the symbolic aspects of language to the edges of discourse and instead enabling something akin to the rhythms and cadences of the Kristevian semiotic to take centre stage. In addition I am attuned to the sound vibrations of my voice in a way that is not available to me when I am focused on its purpose as a carrier of symbolic meaning. I would venture to argue that the listener too might perhaps find him or herself more attuned to the aural and bodily dimensions of my unintelligible utterances than they would be if I were speaking in ‘everyday’ language. However in order to experience this the listener must give up their quest for an intellectual and rational translation of my utterances and perhaps, as Ettinger suggests, be prepared to listen poetically instead. Many therapists are aware that often it is not what is said that ‘touches’ the patient enabling a positive transformation but rather how it is said. As Winnicott stated ‘every analyst knows that along with the content of interpretations the attitude is reflected in the nuances and the timing in a thousand ways that compare with the infinite variety of poetry’ (Wright 31).

It seems then that words themselves are not, perhaps never can be, enough to express fully our lived experiences. Instead it appears that everyday language itself is a barrier preventing access to a more expansive symbolic realm. Antonin Artaud describes his own experience of struggling with the limitations of language

If it is cold, I am still able to say that it is cold; but it may also happen that I am incapable of saying it: that is a fact, for there is inside me something wrong from the affective point of view, and if I am asked why I cannot say it, I shall reply that my internal feeling on this fragmentary and insignificant matter simply does not correspond to the three simple little words which I should then have to utter’ (Esslin 67).

Artaud conveys clearly a disconnection between his inner state and the possibility of articulating it in words. There is for him a gap that cannot be bridged by means of conventional language. Indeed much of his art was spent trying to

communicate the fullness of human experience and emotion through by-passing the discursive use of language and by establishing contact between the artist and his [sic] audience at a level above – or perhaps below – the merely cerebral appeal of the verbal plane (Esslin 70).

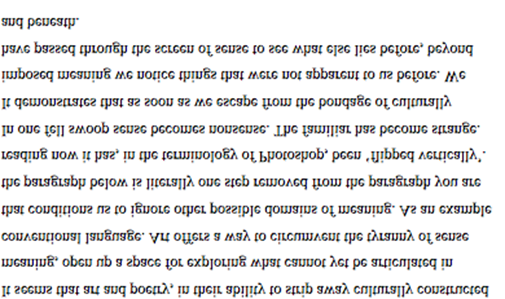

It seems that art and poetry, in their ability to strip away culturally constructed meaning, open up a space for exploring what cannot yet be articulated in conventional language. Art offers a way to circumvent the tyranny of sense that conditions us to ignore other possible domains of meaning. As an example the paragraph below is literally one step removed from the paragraph you are reading now it has, in the terminology of Photoshop, been ‘flipped vertically’. In one fell swoop sense becomes nonsense. The familiar has become strange. It demonstrates that as soon as we escape from the bondage of culturally imposed meaning we notice things that were not apparent to us before. We have passed through the screen of sense to see what else lies before, beyond and beneath.

In this example I sense something of the presence of Derrida’s description of what Artaud called the subjectile

The subjectile: itself between two places. It has two situations. As the support of a representation, it's the subject which has become a gisant, spread out, stretched out, inert, neutral (ci-gît). But if it doesn't fall out like this, if it is not abandoned to this downfall or this dejection, it can still be of interest for itself and not for its representation, for what it represents or for the representation it bears. […] The subjectile resists. It has to resist. Sometimes it resists too much, sometimes not enough. It must resist in order to be treated finally as itself and not as the support or the fiend of something else, the surface or the subservient substratum of a representation (Derrida and Thevenin 52).

In summary it can be argued that art, if we allow it, can enable what we think we know of ourselves and our world, our every day certainties, to be taken out of context and looked at afresh before being assimilated back into our worldview. As such it is capable of assisting us in the formulation of new ways of looking, living and being. As Felix Guattari claims

The work of art, for those who use it, is an activity of unframing, of rupturing sense, of baroque proliferation or extreme impoverishment which leads to a recreation and a reinvention of the subject itself (131).

Works Cited

Bakhtin, M. The Dialogic Imagination. Trans. C. Emerson. Ed. M. Holquist. Austin, Texas: University of TexasPress, 1981. Print.

De Beauvoir, Simone. The Second Sex. Great Britain: Picador, 1988. Print.

Derrida, Jaques and Paule Thevenin. The Secret Art of Antonin Artaud. Trans. Mary Ann Caws. United States of America: MIT Press, 1988. Print.

Esslin, Martin. Artaud. Ed. Frank Kermode. Glasgow: Fontana, 1976. 127. Print.

Ettinger, Bracha. The Matrixial Borderspace. Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press, 2006. Print.

--- "Psychoanalysis and Matrixial Borderspace:" (2007). Web. 6/6/09. <http://www.egs.edu/faculty/video-lectures/egs-video-lectures-2007/>.

--- "Weaving a Woman Artist with-in the Matrixial Encounter-Event." Theory, Culture and Society 21.1. Web <http://tcs.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/21/1/69>.

Guattari, Felix. Chaosmosis: An Ethico-Aesthetic Paradigm. Trans. P. Bains and Julian Pefanis. United States of America: University of Indiana Press, 1995. Print.

Hall, Stuart, ed. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage Publications Ltd, 1997. Print.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982. Print.

Kristeva, Julia. Black Sun: depression and melancholia. United States of America, Columbia University Press. 1989. Print

Pollock, Griselda. "Bracha Ettinger - Resonance/overlay/interweave - Exhibition Catalogue." (2009). Print.

--- "Mother Trouble: The Maternal-Feminine in Phallic and Feminist Theory in Relation to Bracha Ettinger's Elaboration of Matrixial ethics/aesthetics." Studies in the maternal - available online at www.mamsie.bbk.ac.uk 1.1 (2009): 13-13. Web.

Reckitt, Helana and Penny Phelan. Art and Feminism. New York: Phaidon Press, 2006. Print.

Showalter, Elaine. Sexual Anarchy:Gender and Culture at the Fin De Siècle. New York: Viking, 1990. Print.

Stewart, Susan. Nonsense: Aspects of Intertextuality in Folklore and Literature. London: The Johns Hopkins University Press Ltd, 1979. Print.

Wright K. Mirroring and Attunement (Self-Realization in Psychoanalysis and Art). USA: Routledge, 2009. Print.

Bibliography

Adams, Tessa. "Contemporary Art and the Revisioning of Identity." International Journal of Jungian Studies 1.1 (2009): 50. Print.

Bailly, Lionel. Lacan. England: Oneworld Publications, 2009. Print.

Bakhtin, M. The Dialogic Imagination. Trans. C. Emerson. Ed. M. Holquist. Austin, Texas: University of TexasPress, 1981. Print.

Bradley, Arthur. Derrida's of Grammatology. Wilts, England: Edinburgh university press. Print.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble London: Routledge, 1999. Print.

Critchley, Simon. Ethics-Politics-Subjectivity (Essays on Derrida, Levinas, and Contemporary French Thought). London: Verso, 2009. Print.

De Beauvoir, Simone. The Second Sex. Great Britain: Picador, 1988. Print.

'De Zegher, C'. "Gaze-and-Touching the Not enough Mother." Eva Hesse Drawing. Belgium: The Drawing Center and Yale University Press, 2006. Print.

Derrida, Jaques and Paule Thevenin. The Secret Art of Antonin Artaud. Trans. Mary Ann Caws. United States of America: MIT Press, 1988. Print.

Dhar, Anup. "Sexual Difference: Encore, Yet again." Annual Review of Critical Psychology 7 (2009). Web. 12/01/2009.

Esslin, Martin. Artaud. Ed. Frank Kermode. Glasgow: Fontana, 1976. 127. Print.

Ettinger, Bracha. "Fragilization and Resistance." Studies in the maternal - available online at www.mamsie.bbk.ac.uk 1.2 (2009). Web. 11/12/09.

--- The Matrixial Borderspace. Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press, 2006. Print.

--- "Matrixial Trans-Subjectivity." Theory, culture and society 23.May (2006): 218-222. Print.

--- "Psychoanalysis and Matrixial Borderspace: " (2007). Web. 6/6/09. <http://www.egs.edu/faculty/video-lectures/egs-video-lectures-2007/>.

--- "Weaving a Woman Artist with-in the Matrixial Encounter-Event." Theory, Culture and Society 21.1. Web <http://tcs.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/21/1/69>.

--- "Women-Other-Thing: A Matrixial Touch." Ed. Elliot, David and Pamela Ferris. Matrix-Borderlines (catalogue). Oxford: Moma, 1993. Print.

Flax, J. Thinking Fragments: Psychoanalysis, Feminism, and Postmodernism in the contemporary West. Berkley: University of California Press, 1990. Print.

Foster, Hal. "The Return of the Real." The Return of the Real. United States: MIT, 1996. Print.

Guattari, Felix. Chaosmosis: An Ethico-Aesthetic Paradigm. Trans. P. Bains and Julian Pefanis. United States of America: University of Indiana Press, 1995. Print.

Hall, Stuart, ed. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage Publications Ltd, 1997. Print.

Heidegger, Martin. Poetry, Language, Thought. Trans. Albert Hofstadter. New York: Perennial Classics, 2001. Print.

Irigaray, Luce. Je, Tu, Nous. UK: Routledge, 2007. Print.

Kapuscinski, Ryszard. The Other. United States of America: Verso, 2008. Print.

Keynote speakers Judith Butler (Berkeley), Cathérine de Zegher and Christine Buci-Glucksman. Chaired by Griselda Pollock. "Bracha Ettinger Symposium on the Art, Aesthetics and Philosophical Significance of Bracha Ettinger." (2009). Symposium.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982. Print.

Levinas E. Humanism of the Other. United States of America: University of Illinois Press, 2003. Print.

Pollock, Griselda. "Bracha Ettinger - Resonance/overlay/interweave - Exhibition Catalogue." (2009). Print.

--- Generations and Geographies in the Visual Arts: Feminist Readings by Griselda Pollock. London: Routledge, 1996. Print.

--- "Mother Trouble: The Maternal-Feminine in Phallic and Feminist Theory in Relation to Bracha Ettinger's Elaboration of Matrixial ethics/aesthetics." Studies in the maternal - available online at www.mamsie.bbk.ac.uk 1.1 (2009): 13-13. Web.

--- Vision and Difference. UK: Routledge, 1988. Print.

Reckitt, Helana and Penny Phelan. Art and Feminism. New York: Phaidon Press, 2006. Print.

Roman, Camille, Suzanne Juhasz and Cristanne Miller, eds. The Women and Language Debate: A Sourcebook. USA: Rutgers University Press, 1994. Print.

Salih, Sara. Judith Butler. UK: Routledge, 2002. Print.

Showalter, Elaine. Sexual Anarchy:Gender and Culture at the Fin De Siècle. New York: Viking, 1990. Print.

Stewart, Susan. Nonsense: Aspects of Intertextuality in Folklore and Literature. London: The Johns Hopkins University Press Ltd, 1979. Print.

Wright K. Mirroring and Attunement (Self-Realization in Pyshoanalysis and Art). USA: Routledge, 2009. Print.

Zizek, Slavoj. Enjoy Your Symptom: Jacques Lacan in Hollywood and Out. New York: Routledge, 2000. Print.

[1] The Berlin Institute for Cultural Inquiry

[2] It is important to stress that my reflections and thoughts on this voice-based work have come mostly after the event. When initially creating the work it wasn’t from an already well thought out perspective but rather from an insistent inner drive and sense that the work needed to be made.

Received: January 10, 2013, Published: October 28, 2013. Copyright © 2013 Valerie A McLean